Dr Todd Mowery and Justin Yao – Part 1

May 20, 2024Dr. Justin Yao and Dr. Todd Mowery are both Assistant Professors at the Rutgers Brain Health Institute and the RWJMS Department of Otolaryngology. Their research focuses on how the auditory system interconnects with downstream systems to affect cognitive function.

Dr. Justin Yao uses neural circuit manipulations, neurophysiology, and computational approaches to investigate how the auditory cortex integrates with other systems to guide decision-making.

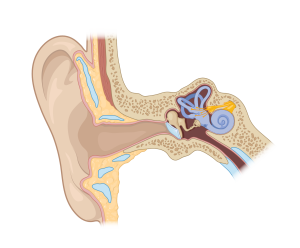

Dr. Todd Mowery uses neuroanatomical, neurophysiological, and behavioral techniques to investigate how hearing loss and vestibular dysfunction impact downstream regions involved in cognitive processing.

In a recent publication (see TDT’s Publication Spotlight), Dr. Yao and Dr. Mowery investigated how vestibular dysfunction affects downstream processes such as decision-making in gerbils. Using various Go-NoGo paradigms with auditory and visual discrimination tasks, the gerbils were tested both before and after receiving surgery designed to cause asymmetrical vestibular dysfunction.

Decision-making, as measured by performance metrics during the Go-NoGo tasks, was significantly affected by vestibular dysfunction, indicating a clear connection between vestibular circuit activity and higher-level processes like decision-making.

Here we discuss the motivation and methods behind the lab’s research focus and this publication in an interview with Dr. Todd Mowery.

How did you get started in research and how did it lead to your current area of focus on the auditory system circuitry?

As an undergraduate, I worked in a psychology lab that did animal research. I had to design a neuroscience major out of biology and psychology. Afterward, I went to Indiana and worked in a primate lab that looked at plasticity in the brain after injury. My PhD focused on somatosensory cortical plasticity after peripheral and central nervous system damage. As a postdoc, I investigated sensory pathways in the rat brain, specifically the striatum and basal ganglion. The research was engaging but had minimal clinical application. So, when a position at NYU opened for studying developmental plasticity in the auditory system, I made the leap. I took my work in the basal ganglia and applied it to the auditory field because there was virtually no understanding of how the auditory signal is passed from the cortex into downstream systems to affect decision-making. This became the foundation for my current work.

What was the central aim of your most recent publication?

The lab focuses on the development of circuits downstream of the auditory cortex and impairments caused by hearing loss.

The lab focuses on the development of circuits downstream of the auditory cortex and impairments caused by hearing loss.

Recently we’ve been looking at inputs between the thalamus, striatum, and cortex during adult hearing loss. The interaction between the auditory and vestibular system is not well known. We’re really interested in how vestibular dysfunction affects other sensory systems, which became the foundation for the paper. We used asymmetrical damage to the vestibular system to see how it affected both auditory and visual decision making.

We ran the easy visual task on the top chambers and the easy auditory task on the bottom and then switched throughout the day. The take-home message of the paper is that you get significant impairments in both easy and hard auditory and visual decision-making tasks.

How did the iCon Behavioral Control Interface help with your research for this publication?

I like the modular nature of the iCon. As new things come out, I’m able to do easy upgrades. It takes 5 minutes to switch a module out.

I was trained to run different classical conditioning tasks. Before the iCon, I would hand train the animals, but now I use the iCon to automate and standardize the training process. Teaching training methods to students is difficult, and bad habits can creep in over time. The iCon eliminates all of that.

I programmed it the way I would train an animal. A novice student can come in, throw an animal in the box, and walk away. And the animals learn in a week or so. This is another feature that has cut down a lot of time in the lab. This frees me to devote my resources to other things.

What about the iPac, which allows you to control multiple behavioral chambers at once?

Quicker training and high throughput testing are the key features that I love. We were able to carry out high throughput behavioral work quickly with the iPac. Previously, I had a single box, so I was running fewer animals and there was no room for error. Developing the paradigm from scratch was a time-consuming process. Now we spend less time testing a paradigm.

The system has surpassed our ability to use it at full capacity. This allows me to have multiple RO1s and actually finish projects on time. With this system I can run 48 animals a day and put that into the grant. My graduate students and postdocs no longer fight over the system.

The system is flexible enough to allow me to run different protocols on different chambers simultaneously. It just depends what I put on the Synapse program, so it’s versatile in that way.

What are your thoughts on Pynapse, the software used to control the system?

I think Pynapse is easy to use if you have a background in Python or other coding languages. The fill-in-the-blank coding gives me a clue as to what options are available and how they work together. We were able to develop the auditory and visual discrimination tasks for the paper within a month, including optimizing the protocol. This would typically take 6 months to a year.

I think Pynapse is easy to use if you have a background in Python or other coding languages. The fill-in-the-blank coding gives me a clue as to what options are available and how they work together. We were able to develop the auditory and visual discrimination tasks for the paper within a month, including optimizing the protocol. This would typically take 6 months to a year.

There is a learning curve to using Synapse and understanding how it works, but I’ve had good experiences with TDT the whole time we’ve been working together. The system is more expensive than other options, but it’s higher quality. And the customer service has been great. Whenever there’s an issue, Myles or Mark jumps on and helps us out. It was nice having someone there to show me how to code at the beginning when I didn’t exactly know what I was doing.

Click to read Part 2 >

Tags: customer spotlight